Brokenwire is a novel attack against the Combined Charging System (CCS), one of the most widely used DC rapid charging technologies for electric vehicles (EVs). The attack interrupts necessary control communication between the vehicle and charger, causing charging sessions to abort. The attack can be conducted wirelessly from a distance using electromagnetic interference, allowing individual vehicles or entire fleets to be disrupted simultaneously. In addition, the attack can be mounted with off-the-shelf radio hardware and minimal technical knowledge. With a power budget of 1 W, the attack is successful from around 47 m distance. The exploited CSMA/CA behavior is a required part of the HomePlug GreenPHY, DIN 70121 & ISO 15118 standards and all known implementations exhibit it.

Brokenwire has immediate implications for many of the 12 million battery EVs estimated to be on the roads worldwide — and profound effects on the new wave of electrification for vehicle fleets, both for private enterprise and for crucial public services. In addition to electric cars, Brokenwire affects electric ships, airplanes and heavy duty vehicles. As such, we conducted a disclosure to industry and discuss in our paper a range of mitigation techniques that could be deployed to limit the impact.

Download

You can download the full paper from the NDSS website.

Cite us

You want to cite our work? Great! Here you can find the bib-file.

Get the code

Our attack and evaluation source code are available on GitHub.

Background

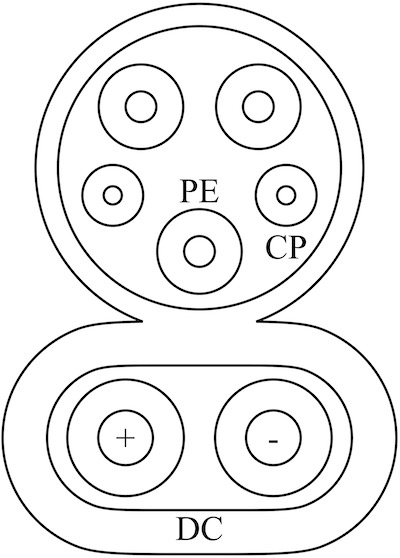

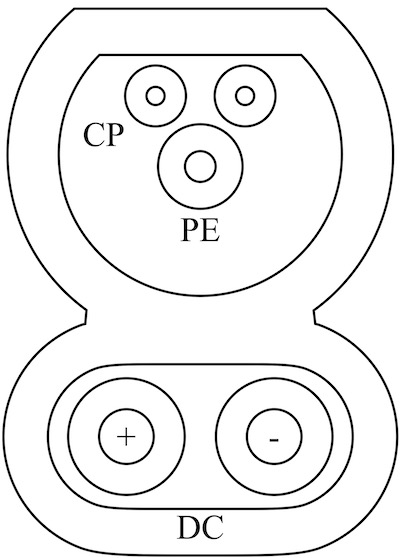

The charging technology standardized as the Combined Charging System (CCS) — the name presented to a vehicle user — is in fact a collection of multiple technical standards. During the charging session, the Electric Vehicle (EV) and the Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (EVSE) exchange important messages, such as the State of Charge (SoC) and the maximum possible current. The high-bandwidth IP link used for the communication is provided by the HomePlug GreenPHY (HPGP) power-line communication (PLC) technology. Depending on the geographical region, CCS uses different plug types which are illustrated in Figure 1. Nevertheless, the underlying technology is the same.

(a) CCS Combo 1 (US).

(b) CCS Combo 2 (EU).

Attack Details

The Brokenwire attack exploits the Carrier-Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance (CSMA/CA) mechanism that is required to be present in any standard-compliant implementation. The CSMA-CA behaviour is repeatedly triggered such that neither vehicle (EV) nor charger (EVSE) ever have an opportunity to transmit. While this action alone could prevent communication indefinitely, it only needs to be applied for a few seconds in order to trigger a timeout in the higher layers of the communication protocol (e.g. ISO 15118). At this point, the entire charging process is aborted and the attacker can stop broadcasting, making it only necessary to have temporary physical proximity to the victim.

Exploiting CSMA/CA

The public HomePlug GreenPHY standard defines Carrier-Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance (CSMA/CA) as a channel access method.

If a node wishes to transmit a message, it will check for other nodes already transmitting.

In case an ongoing transmission is detected, the node will wait for a short, random period of time before attempting to transmit again.

This process is repeated indefinitely, until the transmission medium is idle, and the message can be transmitted.

The Brokenwire attack exploits this channel access mechanism to force the PLC modems at both nodes to endlessly back off and stop communicating.

The attacker continuously transmits a recognizable signal, in this case a preamble, convincing any listening nodes that the channel is busy.

The transmission is repeated indefinitely, such that both modems continue to wait and cannot transfer any data.

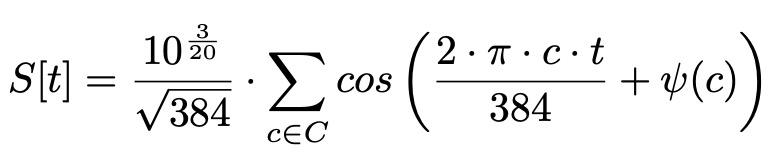

Generating an Attack Signal

In HPGP, the preamble is used to mark the beginning of a frame, to synchronize the receiver's clock with the transmitter and to permit channel state estimation. All frames begin with a standard HPGP preamble, which is sufficient to trigger the CSMA/CA mechanism in nodes that receive it. As such, Brokenwire uses a preamble waveform as an attack signal. The preamble is defined in the standard as a concatenation of repeated preamble symbols, each generated as follows:

Injecting the Attack Signal

As shown by Baker et al., the charging cable acts as an unintentional antenna that leads to electromagnetic emanation. At the same time, this phenomenon makes the charging cable susceptible to electromagnetic interference. Since the cable is unshielded, electromagnetic waves can easily couple onto the wires within it. While the PLC uses differential signaling over two wires, any asymmetries in the two pathways lead to some signal still being retained. By transmitting the attack signal over-the-air, an attacker can therefore cause sufficient coupling on the charging cable of a victim EVSE for it to correctly detect the injected preambles.

Attack Evaluation

Method

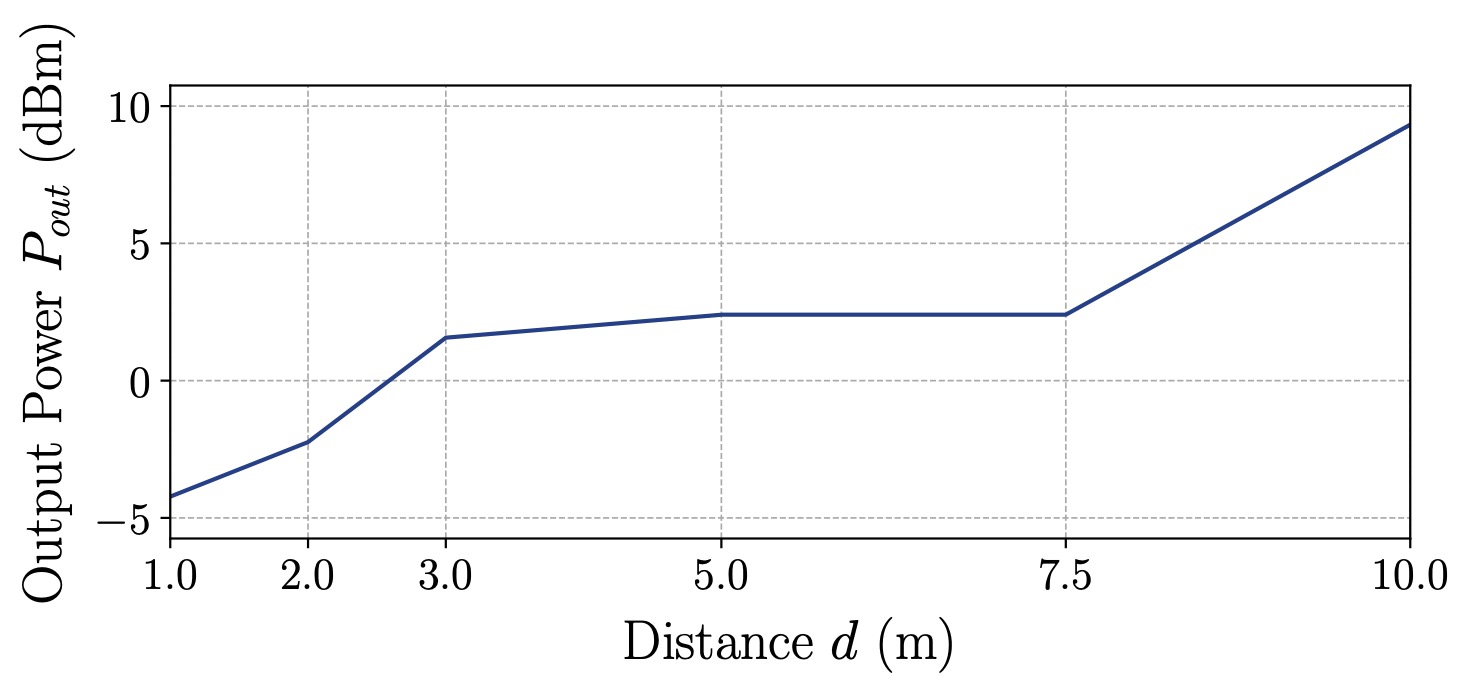

We evaluated the attack in a lab environment under controlled settings for different distances between the charging cable and the attacker. Our testbed was composed of the same HPGP modems found in most EVs and charging stations. On the attacker side, we used a software-defined radio (LimeSDR) together with a 1 W RF amplifier and a self-made dipole antenna. In addition, we tested the attack in a real-world study on eight vehicles from different manufacturers and 20 DC high-power chargers.

Results

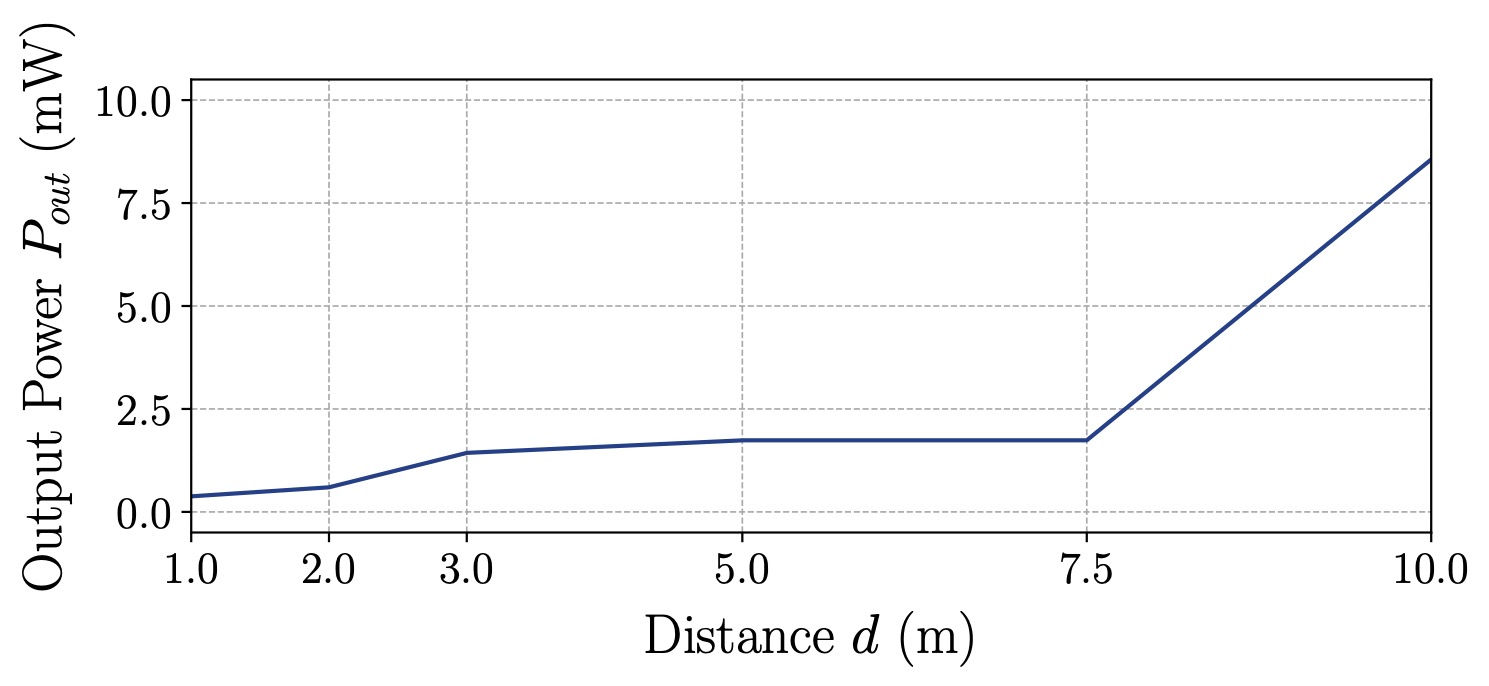

Figure 2 illustrates the results of our lab experiments. Our results indicate that off-the-shelf equipment is sufficient to execute the attack from up to 10 m away. With additional amplification and a total power budget of 1 W, we demonstrated the attack in real-world settings from around 47 m away.

(a) Results in dBm.

(b) Results in mW.

Attack Demonstration

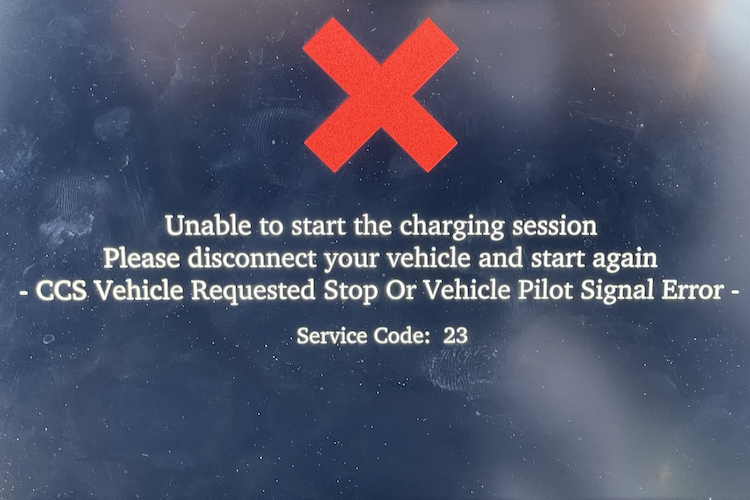

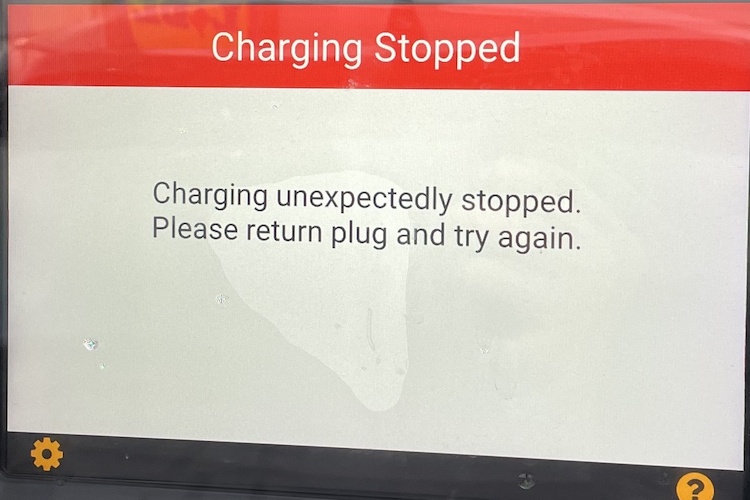

(a) Charger 1.

(b) Charger 2.

Questions & Answers

Why would anyone want to disrupt the charging session?

While it may only be an inconvenience for individuals, interrupting the charging process of critical vehicles, such as electric ambulances, can have life-threatening consequences.

Is my car affected?

Potentially! If your car has a charging port that looks like the one depicted in Figure 1, it is highly likely that the attack also works on your car.

I have a charger at home, can someone stop my car from charging?

Probably not. Most likely your home charger uses AC charging and a different communication standard (IEC 61851), so won't be affected. This might change in the future though, with home chargers getting ISO 15118 support.

Can Brokenwire also break my car?

We've never seen any evidence of long-term damage caused by the Brokenwire attack. Based on our development work, we also have good reason to expect there isn't any.

What can I do to prevent someone from interrupting my charging session?

Right now, the only way to prevent the attack is not to charge on a DC rapid charger.

Wouldn't it be easier to just press the emergency cutout switch or damage the cable?

It depends on the situation. Brokenwire does not require physical access and can disrupt the charging of multiple cars at once from several meters away, making it a stealthy and scalable attack.

Contributors

Sebastian Köhler†

University of Oxford

Richard Baker†

University of Oxford

Martin Strohmeier

armasuisse S+T

Ivan Martinovic

University of Oxford

†Both authors contributed equally to this research.

Ethical Considerations

Given the nature of the infrastructure under investigation, we collaborated with several government entities for our evaluation. We further took precautions to limit any risk of unintentional effects from our testing. We selected only test sites for which no other charging parks were within a reasonable range. We only executed the attack when no other vehicles were charging and could immediately abort the experiments if the conditions became uncontrolled. Outside our closed laboratory sites, we were limited to a maximum output power of 1 W to ensure our attack signal was compliant with all national transmission regulations.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support from armasuisse S+T and EWZ (Elektrizitätswerk der Stadt Zürich).